If you care about the environment, you know that planting trees is one of the best things you can do. Trees help the environment by taking in carbon dioxide and giving oxygen. If you have to get rid of a tree, make sure to only do it a last resort. At Pensacola Tree Services, we are dedicated to helping your home and the environment. We are committed to delivering the best possible service for both. Simply go here for more info Tree Removal in Pensacola

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

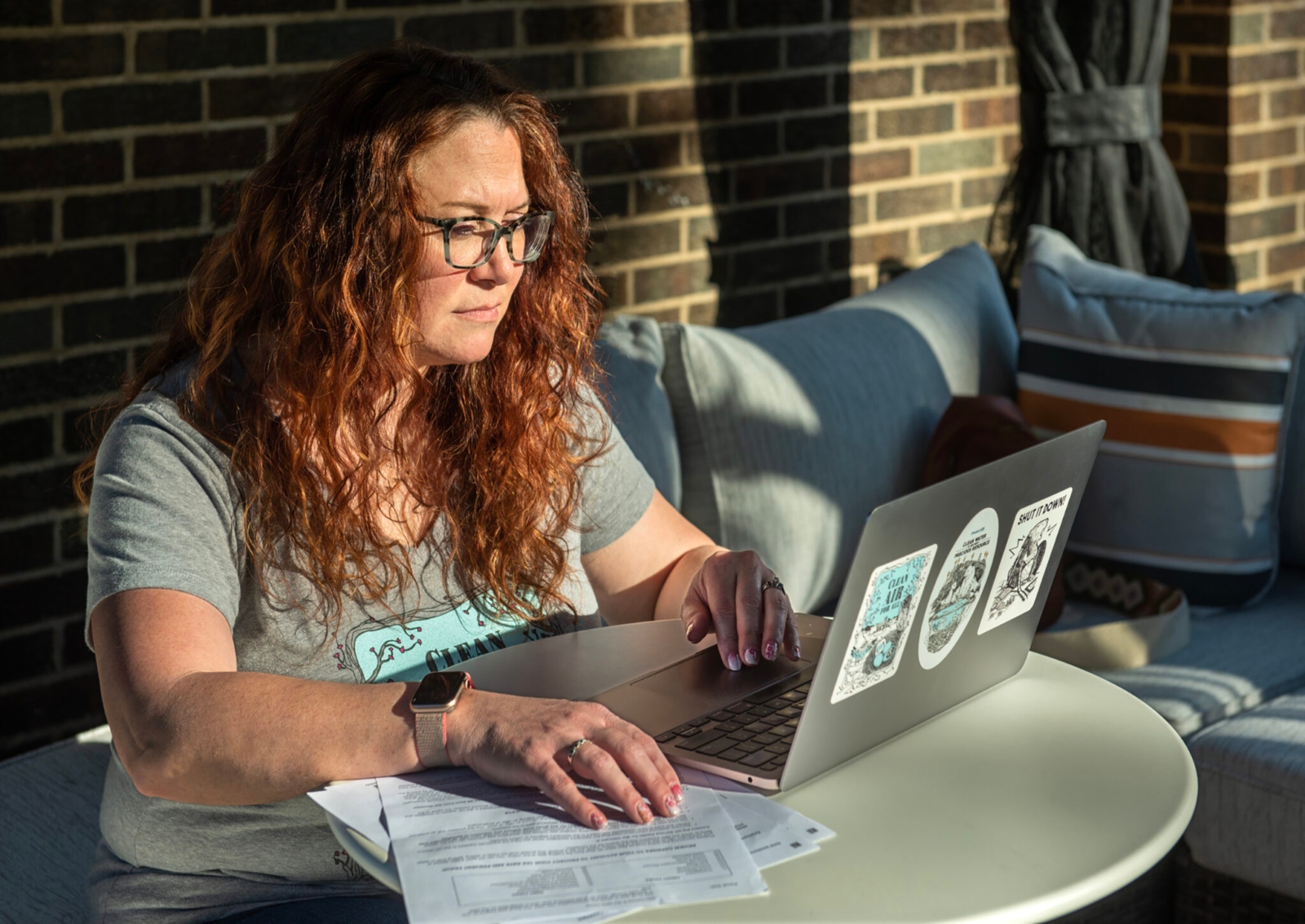

Gillian Graber considers herself an “accidental activist,” a stay-at-home mom who learned in 2014 that a gas company wanted to drill wells 2,400 feet from her house on the eastern outskirts of Pittsburgh and had a vague notion that fracking that close would be dangerous for her two young children.

She started reading everything she could find about the boom in harvesting gas from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. She soon concluded that she was concerned not just about the drilling itself but also about its toxic byproducts. In the fracking process, millions of gallons of water are tainted first by chemicals used to extract the gas and then by potentially dangerous substances that had been safely sequestered in the shale for millions of years until drillers washed them up. Add to that tons of solid waste that can also be toxic. Wells can produce wastewater for decades.

“Holy cow. This is worse than we thought,” she recalls musing after an expert talked to her nascent group of protesters in Trafford, Pennsylvania, about fracking waste.

Considering what to do about drilling waste is not for the faint of heart, Graber soon found. A daunting array of agencies regulate the process, but important loopholes remain. Scientists say they need more facts. Activists who fear fracking and seek cleaner energy collide with neighbors who want jobs, and with a powerful industry that provides a lot of them.

Scott Goldsmith / Inside Climate News

“It’s an extremely complex web of risk and technology, and there’s a need for very strong regulations and enforcement,” said Amy Mall, a senior advocate on the National Resources Defense Council’s dirty energy team who has studied fracking regulation.

The water that comes from gas wells in the Marcellus can contain a long list of substances you’ve probably barely heard of along with poisons like arsenic and naturally occurring radioactive material like radium 226 and 228. It is far saltier than the ocean. That alone makes it deadly to most plants and freshwater life.

Some experts and activists fear that an industry producing a trillion gallons a year of wastewater nationwide—2.6 billion gallons of that were churned out in Pennsylvania last year—is heading for a disposal reckoning.

Drillers in Pennsylvania, second only to Texas in natural gas production, have taken some pressure off by reusing most of their wastewater to drill new wells. But they still took almost 234 million gallons of wastewater last year to injection disposal wells, according to an analysis of state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) data by FracTracker Alliance.

Another 90 million gallons of liquid waste was in “surface impoundment,” most of it waiting to be reused, according to industry reports to the DEP.

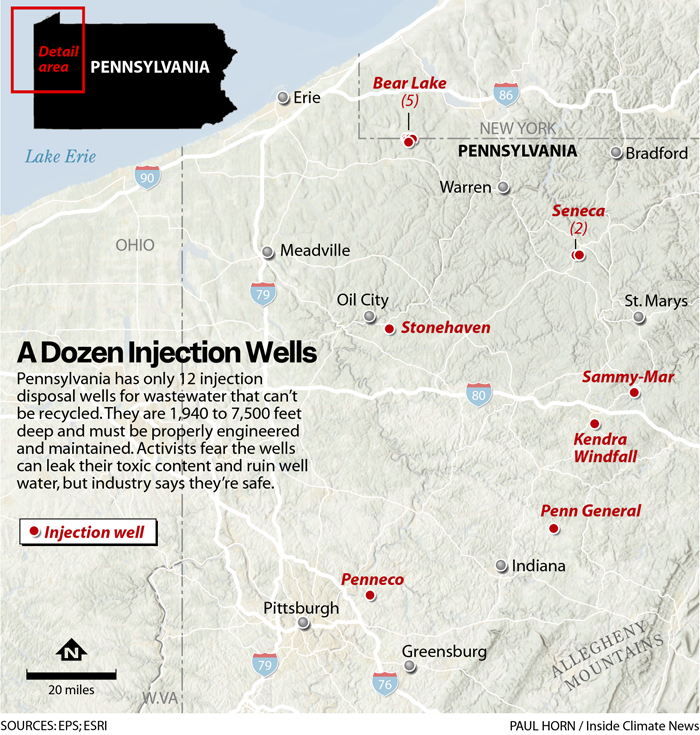

Pennsylvania has only 12 active injection disposal wells for wastewater that drillers can’t recycle. Ohio had 228 in 2021.

Minutes taken at a DEP Oil and Gas Technical Advisory Board meeting in 2021 alluded to a study from Tetra Tech, a consulting firm, saying that Pennsylvania would need between 17 and 34 extra disposal wells to handle the current amount of oil and gas wastewater produced in the state.

In an interview, David Yoxtheimer, a Penn State hydrogeologist who chairs that committee, said that three-quarters of Pennsylvania wastewater destined for wells is trucked to Ohio, where activists are now demanding stricter regulation.

Scientists urge caution about loosening the rules around disposal when they still don’t know everything that’s in fracking wastewater, which is also called produced water.

Some of the nasty chemicals and metals have been studied for toxicity one at a time, but scientists have yet to pin down what they do to people, animals and plants when the exposure is to a rich stew, not one ingredient. There are also questions about what kind of compounds form when all these ingredients meet underground, under pressure, at high temperatures.

“It is toxic,” Radisav Vidic, an environmental engineer at the University of Pittsburgh, said of the wastewater. “I wouldn’t drink it or spread it. I wouldn’t use it for irrigation or livestock. I wouldn’t do anything with it, because it’s bad.” He is trying to develop cheaper ways to clean the water. Current costs are too high to compete with disposal, he said.

A grand jury that investigated problems with the natural gas industry and its regulation in Pennsylvania in 2020 called managing wastewater an “extremely challenging problem” and added, “The fracking industry has never had a good solution for this problem, and it persists today.”

The grand jury, convened by the state attorney general’s office, recommended requiring that trucks carrying wastewater, which now simply say they hold “residual” waste, be emblazoned with a sign indicating where their waste came from. It also said the industry should be required to publicly disclose all of the chemicals it uses to hydraulically fracture or frack wells. It is allowed to keep some secret now.

A report issued by the Environmental Protection Agency after a study of the industry also listed disposal as a looming problem and said that some industry and government leaders favored loosening restrictions. The EPA said some gas company representatives were worried that injection well capacity would eventually be insufficient and noted that regulators might limit use of current wells in the future.

People in arid parts of the country in particular “are asking whether it makes sense to continue to waste this water,” and “what steps would be necessary to treat and renew it for other purposes,” the report said.

The idea of rebranding wastewater from fracking as “a potential valuable resource” was a common theme, it added.

Scott Goldsmith / ICN

The EPA said it has no “activities planned” in response to its report. A spokesperson for the Pennsylvania attorney general’s office said no public action has been taken as a result of its grand jury’s report.

However, Manuel Bonder, a spokesman for Gov. Josh Shapiro, who was attorney general when the fracking report was written, said that Shapiro “supports implementing the report’s key recommendations” and believes “we must reject the false choice between protecting jobs and protecting our planet.”

Richard Negrin, acting secretary of the DEP, has established an internal team to review the grand jury report and “determine the best policies to protect Pennsylvanians’ constitutional rights to clean air and pure water,” the governor’s office said. It is considering a new criminal referral policy to improve “collaboration and efficiency” between the DEP and the attorney general’s office.

A spokesman for the Marcellus Shale Coalition, which represents drillers in Pennsylvania, said he had seen no evidence of disposal capacity problems. In a written statement, the group’s president, David Callahan, said that drillers reuse most of their wastewater, minimizing their need for freshwater and reducing truck traffic.

The American Petroleum Institute Pennsylvania also emphasized the industry’s recycling efforts. “Operators across the country are investing significant time and resources to creatively reuse produced water, use lower-quality water in place of freshwater and build new infrastructure for treatment and conservation purposes,” it said in a statement.

In its 2021 economic impact report, the API said that the oil and gas industry in Pennsylvania directly provided 480,000 jobs and $14.5 billion in labor-related income and contributed $39.4 billion directly to the state’s gross domestic product, providing the gas that powers legions of furnaces, stoves and water heaters that consumers are loath to replace.

“The state’s short- and long-term economic outlook depends on policies that support natural gas and oil development and critical energy infrastructure,” said Stephanie Catarino Wissman, API PA’s executive director.

Dan Weaver, president and executive director of the Pennsylvania Independent Oil and Gas Association (PIOGA), which represents many drillers of older wells, said his members were not finding it hard to dispose of their waste but would welcome more economical options.

To further complicate matters, gas drillers are not the only ones who need space underground. Gas itself is sometimes stored in porous rock during warmer months when demand is low. Companies may also want to store hydrogen or sequester carbon dioxide. Kristin Carter, assistant state geologist in the Pittsburgh office of the Pennsylvania Geologic Survey, said she has been saying for years that the state needs to test its deepest potential storage formations because “the competition for pore space is going to ramp up.”

Graber, the “accidental activist,” co-founded Protect PT, a regional environmental group, and has fought a plan to put wastewater on barges and transport it on rivers near the Ohio border. She has worried about tanker trucks that haul wastewater to deep injection disposal wells in Pennsylvania and Ohio. They could crash and spill their toxic cargo. The wells themselves have caused earthquakes in some parts of the country, including Ohio (though not Pennsylvania).

Scott Goldsmith / Inside Climate News

She has allied with people fighting the addition of a second injection well in Plum Borough, a town of about 27,000 near the Pennsylvania Turnpike’s Monroeville exit. Some residents there say the first disposal well has ruined their well water and created air-quality problems.

Ben Wallace, an engineer for Penneco, the well operator in Plum, said that the facility has not harmed anyone’s drinking water. “The state could use a hundred of these,” he said.

Because recycling used fracking water requires a steady supply of new wells, experts said the need for disposal alternatives will become more obvious if lower prices lead to a slowdown in new drilling.

“What happens when the party stops, and there’s a huge glut of produced water?” asked Seth Shonkoff, an environmental scientist who is executive director of Physicians, Scientists and Engineers (PSE) for Healthy Energy. He said disposal of waste is “an Achilles heel of the industry.”

So far, good, safe alternatives to deep injection, such as effective treatment of the wastewater, are limited by price or regulatory rules.

Many activists want the country to go even further than strictly regulating new wastewater injection wells, by closing the hazardous-waste loophole that allows drillers to dispose of their wastewater with fewer precautions than other industries take. How much fracking waste would qualify as hazardous is not clear, but Mall, the NRDC advocate, said that much of it would.

Maya van Rossum, who leads the four-state Delaware Riverkeeper Network, based in eastern Pennsylvania, wants fracking banned. “There’s no way,” she said, “to make this industry safe.”

Pennsylvania’s extractive history, from coal mining to fracking

Pennsylvania has a long history as a rich source of fossil fuels. Coal mining started in the state in the late 1700s, and the state later became the birthplace of oil production. The first well was drilled in Titusville in 1859.

When commercial gas drilling began in the Marcellus Shale formation in 2004, it was a game changer. The 95,000-square-mile formation extends across New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky. Deep underground, it traps a huge cache of methane—the primary component of natural gas—that was hard to harvest with older techniques.

In 2008, Terry Engelder, a Penn State geologist, and Gary Lash, a geologist at the State University of New York, calculated that the Marcellus contained between 168 trillion and 516 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. They believed the technology of that time could extract at least 50 trillion. That set off a drilling boom that, in the view of some critics, prioritized the rapid capture of a new source of natural gas over methodically studying the environmental impact of fracking or regulating the new industry effectively. Many safety lessons were learned the hard way, and fracking’s reputation suffered.

Pennsylvania, Engelder said, is the “crown jewel” of the Marcellus, the place where more than 80 percent of the formation’s natural gas resides. Drillers have already removed far more than his purposely conservative initial estimate.

The Marcellus was once the bed of a salty, inland sea. As the continents shifted and mountains rose, it wound up far beneath the surface in a distinct layer that is 50 to 400 feet thick in Pennsylvania. Transformed by heat and immense pressure, bits of quartz, mineralogical clay and organic matter became soft, coal-black rock layered like baklava. Small, primitive life forms like algae and plankton became methane, the simplest hydrocarbon, and it lodged in pockets in the rock about 100 nanometers wide, said Engelder, who is now an emeritus professor. For comparison, a human hair is 80,000 to 100,000 nanometers wide. The pores are so small that geologists couldn’t find them with light microscopes. They needed scanning electron microscopes to see them.

Drillers have long known that “fracturing” the rocky storage cells that housed petroleum products increased a well’s yield. Back in the 1800s, Engelder said, drillers would drop nitroglycerin into a well and “blow the living hell out of the rock around it.”

Today’s hydraulic fracturing—fracking—is a remarkable feat of engineering. But the oil and gas industry’s lexicon is studded with turbid jargon that makes it maddeningly difficult for non-engineers to understand the complex interplay between water, drilling and waste.

There are two types of natural gas wells: conventional and unconventional. It is the type of geologic formation, not the type of drilling, that determines which category a well is in.

Conventional wells are drilled straight down into formations of rock such as sandstone or limestone that make natural gas or methane extraction relatively easy. Unconventional wells, which now predominate among newly drilled wells, use more advanced techniques to access gas trapped more tightly in layers of hard rock like shale. These wells are known for their long, horizontal pipes.

Fracking uses a solution of water, sand and chemicals—some of which are toxic—to free the gas. Nowadays, the technique is used in both types of wells, although conventional wells can be fracked with just unadulterated water.

Both types of wells produce wastewater that contains dangerous chemicals and metals and can also be radioactive. The unconventional wells use much more water and produce much more waste. Their waste is often, but not always, saltier and more radioactive.

Scott Goldsmith / Inside Climate News

The wastewater is called “flowback” and “produced water.” The industry also euphemistically calls liquid waste “saltwater” if it’s as salty as the ocean and “brine” if it’s much saltier.

The fracking process starts at the surface, where a drill mounted on a platform begins boring straight down for about 6,500 feet, Engelder said. The hole at the top is 20 inches in diameter, big enough for an 18-inch casing or pipe.

For the first 1,000 feet, the drill is driven by air, like a jackhammer. Air pushes the rock cuttings out of the hole. As the hole deepens, drillers drop in interlocking, watertight segments of steel pipe, most of which are 30 feet long. Like nesting dolls, they become narrower as the well deepens.

No water is used until the drill is below the aquifer—underground water often used for drinking. Aquifers in Pennsylvania are usually 200 to 500 feet below the surface but can be as deep as 1,000 feet. Well below the aquifer, drillers can use a mixture of plain water and thick, viscous drilling mud, a relatively safe concoction, to cool the drill and lift debris. Drilling the entire well requires 50,000 to 100,000 gallons of water.

Once the vertical pipes are placed, workers send a slurry of cement down the hole that then rises to encircle the outside of the pipe. Yoxtheimer, the Penn State hydrogeologist, said that the top 2,500 to 3,000 feet of a new well are encased in at least two layers of cement and pipe, a measure meant to protect drinking water that exceeds precautions taken when the boom began.

At 6,500 feet down—500 feet above the Marcellus—drillers add a bent pipe at the end that introduces a gradual curve like an elbow in an extremely long straw. Steel pipes hanging from a drilling platform, Engelder said, are flexible like spaghetti and can bend over the next 500 feet until they reach the Marcellus and level out roughly perpendicular to the vertical shaft. The process of adding section after section goes on for about 10,000 horizontal feet, almost two miles. (In 2008, lateral pipes were just 2,000 to 3,000 feet long. Some modern wells extend five miles laterally.) By the end, the pipe is just six inches in diameter.

The Marcellus introduces a challenge at this step because it is not perfectly perpendicular to the vertical casing. How do the crews keep their drill inside this layer? The answer lies in one of the Marcellus’s characteristics that makes wastewater dangerous. Unlike harder layers above and below it, it’s radioactive, thanks to deposits of thorium, uranium, potassium-40 and radium, and the gas is richest in areas with the most radiation. A device that measures gamma rays guides the drill.

Once the horizontal pipe is finished, it’s time to perforate the horizontal casing using a device that shoots bullets through the pipe, leaving holes a little smaller than a dime, Engelder said. It makes clusters of 12 to 16 holes every 50 feet.

All this takes about a week of round-the-clock work.

Finally, the fracking, which takes another week or so, begins. The drillers pump 15 to 20 million gallons of water and fracking chemicals into the casing under pressure so intense that, if you aimed it at your house, “it’d just blow right through it,” Engelder said. Water shooting through the holes in the pipes fractures rock 500 or more feet away, Yoxtheimer said.

The added chemicals, which constitute about 0.5 to 2 percent of the mixture, are what make environmentalists start to worry. Engelder said the known ingredients usually include an acid, a biocide or disinfectant, ethylene glycol to prevent scaling or forming hard particles, latex polymer to make the water more slippery, ammonium bisulfate to inhibit corrosion and guar gum, a thickening agent that’s also used as a food additive.

During the first week or two after fracking, operators let water known as flowback drain from the well slowly so that sand, used as a “proppant” to hold the rock apart while the methane escapes, doesn’t come up with it, Vidic said. Gas can’t escape while water fills the well.

This flowback contains the initial additives plus chemicals and minerals it picked up while coursing through the Marcellus. Once the well starts producing gas, the water that comes from deep underground is called produced water. Because it has had more time to dissolve elements of the shale and percolate in the Marcellus, it contains a higher concentration of chemicals.

Only about 5 to 10 percent of the water used to frack a well initially comes back to the surface. In this sense, Pennsylvanians are lucky that the Marcellus is a dry formation that absorbs much of the fracking fluid.

In some other parts of the country, drillers get back more water than they put in. However, Yoxtheimer said the wells produce water for decades, until they are plugged with cement. Eventually, they will yield about half of the fracking fluid while the rest, Engelder said, settles into the pores in the Marcellus that the methane vacated.

The wastewater and gas are collected—and separated—at the drill pad. Liquid is usually stored in onsite tanks until it’s reused or trucked somewhere else. Gas companies often drill multiple wells 10 to 20 feet apart on one pad. One drill pad with six wells can drain a square mile, Engelder said.

In fracking’s wastewater, toxins present unknown risks

In Pennsylvania, drillers report most of their fracking ingredients to FracFocus, a website the industry began using for disclosure after activists demanded more information. The formulas are different for each well, and hundreds of different additives may be used.

Late last year, for example, the operator CNX Gas reported on 17 specific chemicals and three “trade secrets” added to more than 16 million gallons of water it used to frack a well in Westmoreland County. Some of the chemicals are considered hazardous or flammable. Some are toxic to aquatic animals or people under certain circumstances. One, methanol, may cause birth defects with chronic exposure.

Scientists said they know that there are often dangerous constituents in produced water, but ingredients vary by well and by part of the country.

“Frankly, what most concerns me is what we don’t know,” said Bernard Goldstein, an emeritus professor of environmental toxicology at the University of Pittsburgh and a former EPA official. For years, he has asked, “Hey, what’s the rush?”

The oil and gas industry benefits from a 1988 federal EPA decision to exempt the politically powerful oil and gas industry from hazardous waste provisions of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act and a 2005 federal law that allows drillers to keep some of their drilling chemicals “proprietary” and exempt from public reporting. (Pennsylvania requires them to disclose the secret ingredients to the DEP but doesn’t tell the public.)

Scott Goldsmith / ICN

The wastewater may include radioactive materials from the shale as well as other naturally occurring substances such as arsenic, barium, strontium, chloride, bromide, iodide, iron, manganese, calcium and magnesium, said John Stolz, director of the Center for Environmental Research and Education at Duquesne University. Methane itself is not toxic to people, but it is flammable and a potent greenhouse gas.

Yoxtheimer said a modern Marcellus well could also generate as much as 400 tons of salt during the flowback period. Fracking wastewater, he said, must be tested before disposal for 52 different compounds including radioactive radium. “It’s literally everything from arsenic to zinc,” he said. Representative samples from a county are taken at well pads and sent to a lab for analysis “at least annually,” he added.

While some researchers have found that fracking safety in Pennsylvania has improved markedly in recent years, any process is subject to human error. Equipment can sometimes fail, so operators must be vigilant. “Any time people are involved, all bets are off,” the University of Pittsburgh’s Vidic said.

In its 2021 report on fracking, the DEP said it found 8,663 compliance violations among oil and gas operators. Of those, 2,826 were administrative, 1,323 were for unconventional drillers and 4,514 were for conventional drillers. The report said there were 5,898 health and safety violations that year.

The department recently issued a strongly worded report on a rampant failure of conventional drillers to report required information on time, poor performance that DEP attributed to a “culture of noncompliance.” It said it would need more money to police the conventional industry.

The report said that, from 2017 to 2021, 11.7 percent of conventional wells inspected had violations. Less than 30 percent of operators reported production or mechanical integrity assessments on time. The most frequent health and safety violation was improper abandonment of oil and gas wells.

“People should be screaming about that,” David Hess, a former DEP secretary who now writes an environmental blog, said of the poor reporting. He noted that self-reported data from drillers in Pennsylvania has never been audited.

Weaver, the PIOGA leader, said the state had major problems with its reporting system.

In DEP’s 2022 oil and gas data, operators reported 28,193 tons of soil contaminated by wastewater spills. Conventional drillers also reported that they had spread 5,460 gallons of liquid waste on roads. Hess said road spreading was long allowed and has been found to result in soil contamination. It is not technically banned now, but he knows of no drillers with permits to do it. Sources tell him that the practice has not stopped.

“That stuff is running into a ditch,” he said. “That ditch goes to a stream.”

While lay people often focus on potential problems with the wells themselves, experts have broader concerns. Yoxtheimer worries about spills from storage tanks. Most reported spills at fracking well pads are small, what he called “mosquito bites.” Five to 10 gallons spill on the drill pad and are vacuumed up. But something like a broken valve can cause a much bigger spill. He said he hasn’t heard of one of those incidents for at least five years.

Isabelle Cozzarelli, a research hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, Virginia, studied the aftermath of a 2.9-million-gallon wastewater leak from a pipeline in North Dakota in 2015, so pipelines are always top-of-mind for her. The liquid is not only toxic itself, she said, but can also cause secondary reactions in soil and streambeds that release other dangerous substances, such as arsenic, from rocks. She is now studying the illegal dumping of wastewater on Bureau of Land Management land in New Mexico.

Stolz, the Duquesne University expert, worries that the salts, heavy metals and radioactivity in drill cuttings and other solid fracking waste could be “turning landfills into potential Superfund sites.”

He is also among those who want stronger labeling for trucks that haul wastewater. He said he had seen tanks on drill pads that hold produced water labeled with placards that say it poses a health and fire hazard. But when operators need to move that water, he said, they use a “magic hose” to put it in a truck that gets only a “residual waste” sign.

Many activists and the attorney general’s grand jury have said that such low-key signs downplay how dangerous the waste could be to first responders to a truck accident.

Yoxtheimer said many emergency personnel have been well trained in how to handle the waste.

Matt Kelso, manager of data and technology for FracTracker, said that the data currently reported make it difficult to know when trucks carrying fracking waste have accidents that involve spills.

Yoxtheimer said trucks can roll over, spill their load and contaminate soil. “It’s not widespread,” he said, “but it has happened.”

A murky disposal picture. Are injection wells the solution?

Assessing the wastewater disposal situation is difficult, at least in part because state rules on disposal are a mishmash, activists said. For starters, operators of newer unconventional wells face tougher regulation than those who drill conventional, vertical wells. Numerous experts interviewed were unaware of any measures of the capacity of current disposal wells in Pennsylvania and Ohio. The DEP did not respond to most questions about wastewater disposal and other issues related to fracking.

In the early, wild west days, unconventional frackers sent much of their water to municipal water treatment plants as conventional drillers had done for decades. It soon became apparent that the municipal plants couldn’t handle the extra volume and salts, and that practice was banned—but only for unconventional drillers. There are a handful of specialized treatment facilities that could clean some fracking wastewater, but observers said they are not widely used by unconventional drillers.

In the early fracking years, drillers often stored wastewater in big, lined pools known as centralized impoundments. Because of leaks, the old ones had to be “closed out,” Yoxtheimer said.

While the pools are still legal, most companies don’t use them now because of tougher regulation. Companies are more likely to use storage tanks now.

Scott Goldsmith / Inside Climate News

Recent data on disposal is confusing and incomplete.

In its 2021 report on the fracking industry, the DEP said that 93 percent of wastewater was being recycled or reused at new wells. This liquid could require some treatment, with the wastewater mixed with freshwater before it is reused. Seven percent of wastewater was being sent to injection wells, the state agency said.

Data reported to DEP for 2022 and analyzed by FracTracker showed that only about 50 percent of the wastewater for both conventional and unconventional wells was definitely being recycled. Another 38 percent was assigned to categories where most of the water is reused or recycled. DEP did not respond to a question about how much of the water in those categories, which include liquid sent for waste processing and surface impoundment, is reused. The report showed 8.8 percent of wastewater going to injection wells.

For now, most experts view injection wells as the safest disposal alternative.

“The best thing to do is to put [the wastewater] underground, but to put it back underground in places that are deeply informed by hydrogeologic conditions,” Shonkoff said.

Injection wells can either be newly drilled specifically for waste disposal or old conventional wells that are refurbished for disposal. Expert opinion on which type is better is divided. The EP did not respond to a question about how many of its wells were created just for waste, but records show that at least half are converted older wells.

Pennsylvania’s disposal wells are 1,940 to 7,500 feet deep, according to the geological survey’s Carter. What’s most important for safety, experts said, is for these wells to be in the right place and engineered and maintained properly.

First, the wastewater must go to rock that is porous enough to accept it. That layer needs to be well below any underground water and bounded at the top and bottom by hard rocks that will hold the wastewater in place. The well itself needs to have uncorroded metal at its core with solid cement around it to further protect the aquifer.

Waste is only allowed to go into the well at a certain rate and pressure. Drillers are required to monitor for signs that wastewater is escaping. Operators need to know about other wells in the area because wastewater can migrate underground and it seeks places with low pressure. “Water will follow the path of least resistance,” Stolz said. For that reason, unplugged, abandoned wells can be a hazard.

The University of Pittsburgh’s Vidic said he thinks it’s best for disposal wells to be deeper than most old conventional wells. Injecting waste into the same formations that old wells tapped increases the risk that wastewater will find a route to the surface, he said.

By the time Pennsylvania learned that its unconventional drillers needed more injection wells after being turned away from municipal treatment facilities, residents were less enamored with fracking and more frightened of its waste.

Some of the few attempts to create new injection wells in the state have met with opposition. In one notable instance, Grant Township in Indiana County has been fighting a proposal to repurpose an old gas well since 2014. That case has now gone to the state Supreme Court.

In Plum Borough, outside Pittsburgh, residents who did not stop the town’s first injection well are fighting Penneco’s proposal for a second. Robert Teorsky has filed a lawsuit alleging that the first well, named Sedat 3A, led to contamination of his water. In his suit, he said his property line is 1,500 feet from Penneco’s “operations.” His lawyer did not return a call.

Katie Sheehan, a 36-year-old nurse who lives 500 feet from Sedat 3A, has been one of the most vocal opponents. Her house once belonged to her grandmother, who used well water. Her father, who gets his water from a spring, also lives nearby.

She said water quality at both houses suffered after the injection well began operating. Her water turned cloudy and orange. She hired a testing firm that found impurities. She filed numerous dead-end complaints.

Sheehan, who sounded weary and frustrated, now trucks in clean water and said she is afraid to have children because of air and water problems she believes come from the injection well.

“I understand that it has to go somewhere,” Sheehan said of the well. But she thinks injection wells should go to less populous areas.

Wallace, the Penneco engineer, said he understands why neighbors often have qualms. But he thinks injection wells are safe and said that the permitting process is so detailed in Pennsylvania that it costs about half a million dollars. “We’re highly regulated,” he said. “We’re inspected on a regular basis.”

Wallace said Penneco did pretest neighbors’ water before its existing injection well began operating. Sheehan had not yet moved to her house and her family declined the testing, he said. He said that DEP testing found no evidence that his well had contaminated her water.

Pennsylvania needs far more disposal space for its gas wastewater, which is why so many trucks now head to Ohio from Pennsylvania, Wallace argues. “The state of Pennsylvania is woefully behind in injection wells,” he said.

Because Ohio never allowed drillers to use water treatment plants, demand for injection wells was much higher there from the beginning of the fracking boom. It was also cheaper to create injection wells in Ohio, because layers of suitable rock there weren’t as deep as they are in Pennsylvania, said the geological survey’s Carter.

Getting a well approved in Ohio or West Virginia is also simpler, requiring only a go-ahead from state governments because both have “primacy.” A new well in Pennsylvania must be approved by the EPA and then by the DEP. A DEP official said in mid-March that Pennsylvania was considering applying for primacy as well. So far, it has given notice only that it will seek primacy for wells able to sequester CO2 underground.

But in part because of that more streamlined regulatory environment, opposition is mounting among residents of Ohio as well. A group of environmental and civil rights organizations is now calling for tougher regulation of injection wells and enforcement of violations. James Yskamp, a senior attorney with Earthjustice who was involved in a petition to the EPA seeking tighter oversight, said Ohio’s citizens have been “bearing the brunt of waste disposal” while largely being cut out of the approval process.

The disposal wells, he said, are “deeply unpopular” in communities—even more unpopular than the fracking wells themselves.

The petition, submitted by Earthjustice in October, said the wells disproportionately affect low-income communities and that Ohio failed to properly map underground sources of water that could be affected by injection wells. It said wastewater has migrated underground from an injection well to conventional oil and gas wells as far as five miles away and surfaced there. One of the wells where wastewater surfaced was abandoned and unplugged, like many in Pennsylvania.

In January 2021, wastewater spurted from an idle well 2.5 miles away from two injection wells. “For four days, the idle production well spewed more than 40,000 barrels [a barrel equals 42 gallons] of waste across the ground and into a nearby stream, killing approximately 500 fish and aquatic species,” the petition said. “These incidents all could have seriously impacted Ohioans’ drinking water.”

The petition also says that seismic activity associated with the wells has “increased dramatically” in Ohio over the past 15 years.

Activists want Pennsylvania to stop playing ‘catch up’

What happens next depends to some extent on whether natural gas is seen as an imperfect but necessary transition to greener energy or a big speed bump in the fight against climate change.

Natural gas is cleaner than coal, notes Engelder, who runs his property outside State College on solar energy most of the time but still needs to buy electricity at night. Doing entirely without fossil fuels, he said, would have people living like they did before the Industrial Revolution. “All of us enjoy a lifestyle,” he said, “that is largely a consequence of burning fossil fuels.”

Vidic, the University of Pittsburgh environmental engineer who is trying to develop ways to clean the wastewater, thinks energy independence is good foreign policy for the United States.

But van Rossum, head of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, wants fracking banned, as it has been in New York.

Since there’s no indication that fracking in Pennsylvania is going away anytime in the immediate future, activists and academics say more research is needed on what is in wastewater, how to clean it up, and how to dispose of the liquid and solid waste safely.

Cozzarelli, of the Geological Survey, said that if people don’t know what’s in the wastewater, it’s hard to make it safer. Goldstein, the emeritus Pittsburgh professor, thinks more high-quality research should be done on how fracking and wastewater disposal affect people near wells over time.

Some talk of harvesting valuable components of wastewater like lithium, a move that could change the economic calculus for wastewater treatment.

On the policy side, Penneco’s Wallace is a voice for streamlining applications for new injection wells in Pennsylvania. And the Marcellus Shale Coalition’s Callahan said in a written statement that the industry already has a “strong regulatory environment.” The group said it would continue working with regulators “on advancing frameworks and best practices aligned with our shared goal of developing natural gas responsibly.”

Many activists, on the other hand, want stricter, more consistent regulation with more enforcement.

“We should be very vigilant about produced water of unknown toxicity being discharged to the surface, and water that is injected into the ground should be proven not to intermingle with our drinking water,” Shonkoff said. “That is probably the best that we can do right now.”

The country could go further, activists said, by closing that hazardous-waste loophole for oil and gas waste. That would trigger tougher regulation for the most dangerous fracking waste and restrict it to different types of disposal wells and landfills.

State Sen. Katie Muth, a Democrat who represents parts of three counties near Philadelphia, has introduced three bills this year that would “update the state Solid Waste Management Act to hold the oil and gas industry to the same waste regulations as other industries and would keep harmful radioactive toxins out of Pennsylvania’s air, groundwater, waterways and drinking water supplies across the state,” a spokesperson said.

A fourth bill to be introduced later this year would require trucks carrying drilling wastewater to be “labeled appropriately.”

Hess, the former DEP secretary, argues that self-reported data from both unconventional and conventional drillers in Pennsylvania needs to be audited by regulators. “They could say anything,” he said of the drillers.

Regardless of how the waste is labeled—residual or hazardous—the state could make it safer, he said, by requiring “cradle-to-grave tracking.” He would also require more testing before transport. “Any time you’re transporting stuff that you may not know what’s in it, it presents a risk,” he said.

Hess said Pennsylvania regulators are always playing “catch up” as drillers change their techniques. He pointed to a “frack-out” last June in Greene County in southwestern Pennsylvania. Lisa DePaoli, communications manager for the Center for Coalfield Justice, said residents had reported that water came out of an abandoned, unplugged well in the hamlet of New Freeport “like a geyser.”

They later learned that a well where the gas producer EQT Corp. was fracking a mile away was “communicating” with the abandoned well. A spokesperson for the company said that this information came from a DEP inspection and that EQT was still investigating whether the two wells are connected.

Twenty to 30 households live near the abandoned well, and many get their water from wells or springs. Some said their water changed after the event and that they have since used bottled water only. The EQT spokesperson said that “water sampling and well monitoring have shown no other areas of concern at this time.”

Under Pennsylvania law, Hess said, drillers are assumed to be responsible for contamination of private wells within 2,500 feet of a wellhead. But lateral wells are now longer, and the New Freeport residents lived well beyond 2,500 feet from the site.

Hess also maintains that conventional and unconventional drillers should play by the same rules. “The only reason they don’t have the same regulations is political,” he said.

Activists acknowledge that tougher regulations might increase costs for drillers. That’s not a bad thing, they argue, if you want to even the playing field with greener energy sources.

Mall said the gas industry can afford to pay more. “It’s an industry that’s quite profitable,” she said, “and they can afford to take responsibility for their own dirty waste.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Amid fracking boom, Pennsylvania faces toxic wastewater reckoning on Apr 30, 2023.