If you're concerned about the environment, you're aware that planting trees is one of the most effective things you can do. Trees absorb carbon dioxide and provide oxygen, which helps to preserve the environment. If a tree has to be removed, then be sure it's a last resort. https://www.linkedin.com/in/TreeRemovalPensacola/ provides stump grinding, tree trimming, and stump removal.

For centuries, the Okefenokee Swamp has been a haven for people, animals, and plants. The wilderness, which straddles the Georgia-Florida border, is a mire of winding, midnight waters, giant cypress trees cloaked in Spanish moss, and peat islands floating among alligators and lily pads. The swamp has seen many chapters: It was part of the homelands of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation before the Tribe was forcibly removed from Georgia in the 1820s and 1830s. A hundred years later, the swamp came under federal protection as a national wildlife refuge.

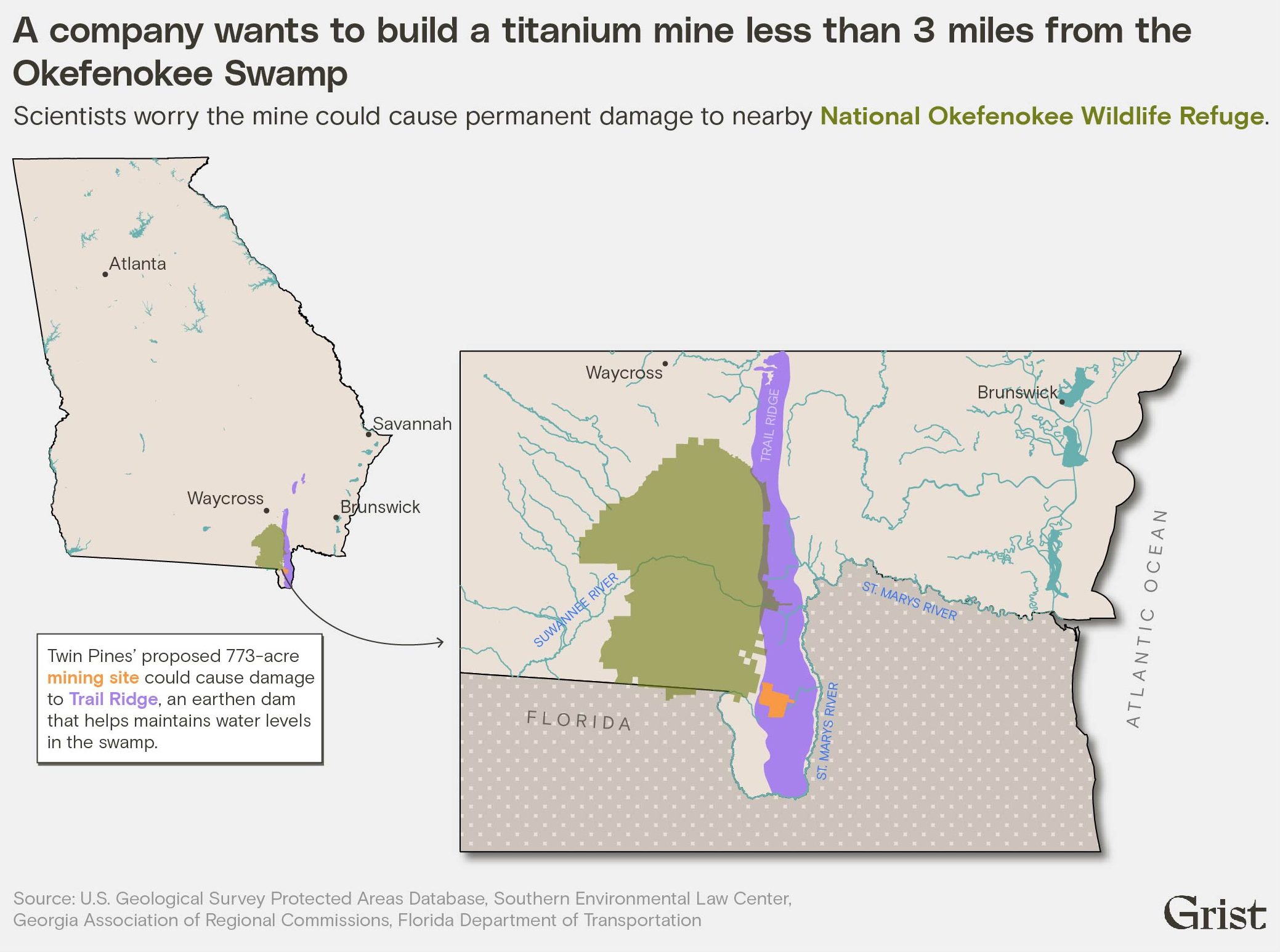

Now, yet another chapter may be approaching for the Okefenokee watershed: a titanium mining site.

For years, the Okefenokee Swamp has been warding off Alabama-based Twin Pines Minerals, which in 2019 filed for permits for a mining project just outside of the refuge. The company hopes to extract titanium dioxide, which can be used to create bright white pigments used in a wide variety of consumer and industrial products. While the swamp itself is not at risk of being turned into a giant mining pit, the project would result in a 500-by-100-foot pit in the nearby Trail Ridge, which holds the swamp waters in place.

This January, the mine moved one step closer to breaking ground when the Georgia Environmental Protection Division released a draft plan for the development and opened a 60-day period of public comment. The progress was made possible by a short-lived Trump administration rule that created a window of opportunity for industrial projects to proceed along protected waterways — even without a federal permit.

“What we’re seeing at Twin Pines is not the only example of waterways that remain at risk because of the prior administration’s rule,” said Kelly Moser, senior attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center, of the Okefenokee Swamp. “It is the most striking example, given that it jeopardizes one of our most iconic and valuable natural resources, but it is not alone.”

During Trump’s time in office, the federal government rolled back hundreds of environmental protections, enacting many new pro-industry policies. Among those was the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which removed the protection of the Clean Water Act — aimed at preventing water pollution — from huge swaths of streams and wetlands across the United States.

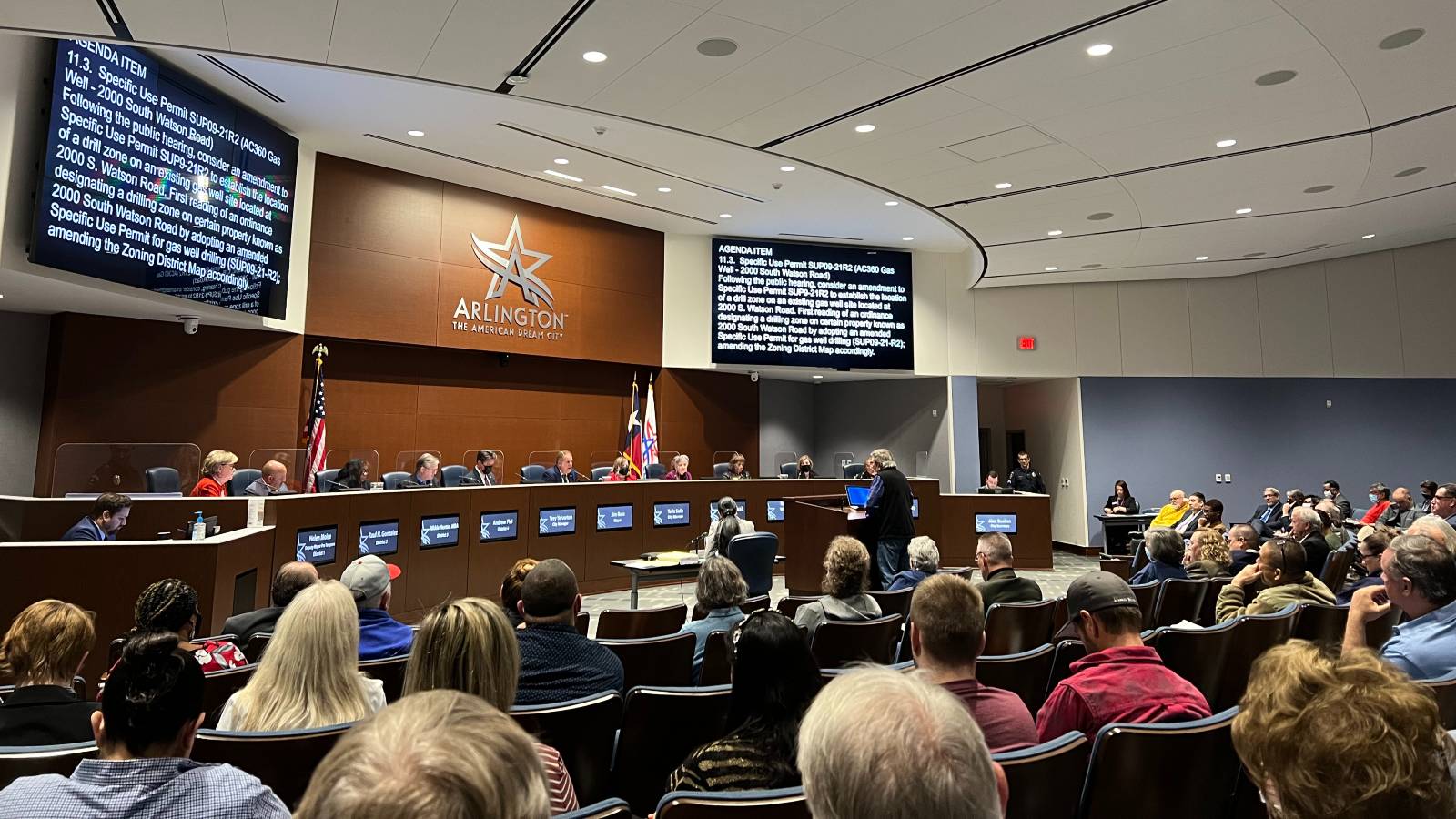

Steve Brookes / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The rule lasted just over 16 months before it was vacated by a federal judge who cited “fundamental, substantive flaws” in the rule. But the damage had already been done: During that time period, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers reported a three-fold increase in projects that no longer needed federal permits. At least 333 of those projects would have required a permit had it not been for the rule.

Companies were trying to take advantage of “the fast food window” to grab their project clearances, said Stu Gillespie, a supervising senior attorney with Earthjustice. (The nonprofit has been involved in litigation against the Army Corps of Engineers and mining companies as a result of the Navigable Water Protection Rule.) He said these projects are likely to have environmental, cultural and potential health consequences that will play out over decades.

“The harms are irreparable,” Gillespie said.

For the Twin Pines mining site, the Trump-era rule meant that for a brief but meaningful window, all the waters associated with the project site were abruptly excluded from federal protection. During that period, the Army Corps of Engineers determined the project only required state approval, a small hill to climb compared to the regulatory mountain that is the federal Clean Water Act, in order to proceed.

Drew Angerer / Getty Images

As with other projects where all the waters were determined not to be under federal protection during that period, the Corps’ decision at Twin Pines has been allowed to stand despite the fact that the rule they were based on is no longer in place. For projects where the federal government still had jurisdiction under the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, many of these had to go back to the starting line.

Scientists from the University of Georgia as well as the Fish and Wildlife Administration have warned against the Twin Pines project moving forward. In 2019, in a document obtained by the Defenders of Wildlife and shared with Grist, the Fish and Wildlife listed concerns about the project’s impact on water levels in the Okefenokee, increasing the likelihood of fires, and destroying habitats. “The effects of the action may be permanent to the entire 438,000-acre swamp and nearby ecosystems on nearby Trail Ridge,” the agency wrote.

Moser called the situation “an absurdity.” The Corps “is not protecting critical wetlands that have been waters of the United States and are waters of the United States,” she said.

Across the country, about an hour south of Tucson, Arizona, another mining complex is already breaking ground as a result of the Navigable Waters Protection Rule. The Copper World Complex is owned by Hudbay Minerals, a Toronto-based mining company. Just like Twin Pines, the Trump-era rule allowed Hudbay to proceed without the need for a federal permit. Within the complex, ephemeral waterways — dry stream beds that turn into rivers or streams after periods during the monsoon season — weave through the slope of the Santa Rita Mountains. These waterways are essential to maintaining surface water levels of the Santa Cruz River, but were categorically excluded from protection under the Navigable Waters Protection Rule.

Still, the two projects have faced multiple legal stumbling blocks. In June 2022, the Army Corps of Engineers identified the proposals in a memo rescinding its previous determinations as a result of the agency’s previous failure to consult local tribes: the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Georgia, and the the Tohono O’odham Nation, Pascua Yaqui Tribe, and Hopi Tribe in Arizona. But after Twin Pines filed a civil suit, the Corps reinstated its Trump-era determination for that site, putting the fate of the project back in Georgia’s hands.

The Corps seems to have applied the same thinking to Hudbay’s Arizona mining project. “Unlike Twin Pines, there hasn’t been any kind of out-of-court settlement with Hudbay or anything along those lines,” said Earthjustice’s Gillespie. The progress in the Copper World Mining Complex is “a direct result” of the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, he said.

Joe Sohm / Visions of America / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Under the guise of Trump-era guidelines, Hudbay has already begun development in the Santa Rita Mountain range, filling the stream beds that are technically back under federal protection.

In November 2022, the Southern Environmental Law Center filed a lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers, arguing the agency was in charge of protecting “waters of the United States,” such as the freshwater wetlands on which the Twin Pines mining site might be built. But at the state level, there are no Georgia laws protecting freshwater wetlands. “The state has always abdicated that responsibility to the federal government,” said hydrologist and University of Georgia professor Rhett Jackson.

In order to proceed, both Twin Pines and Hudbay await only a handful of state permits from Georgia and Arizona, respectively. These permits are related to air quality and groundwater withdrawals, but do not need to address any potential waterway destruction or pollution associated with mining.

In Arizona, state law restricts its own water department from regulating streams not under federal protection. But the Environmental Protection Agency has begun an investigation into the Copper World site to “determine whether there’s been violations to the Clean Water Act,” Gillespie said.

In Georgia, the project must first hurdle the 60-day period of public comment, which began January 19, for Twin Pines’ draft mining plan. With the fate of the Okefenokee Swamp at risk, voices have risen up against the mine both locally and nationally, with opposition likely to reach a fever pitch over the next few months.

Jackson is one of those opposed to the project. “I have traveled all over the world (29 countries), hiked in many national parks, and worked as a wilderness ranger in the North Cascade Range of Washington State, and I have never seen anything more beautiful than the Okefenokee Swamp,” he wrote in an email to Grist.

Stacy Shelton / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Meanwhile, Twin Pines sees the period of public comment as a victory: It moves the project forward.

“We are pleased to have reached this important milestone in the permitting process and appreciate the Georgia [Environmental Protection Division] EPD’s diligence in evaluating our application,” said Steve Ingle, president of Twin Pines Minerals, in a statement. “This is a great opportunity for people to learn the truth about what our operations will and will not do, and the absurdity of allegations that our shallow mining-to-land-reclamation process will ‘drain the swamp’ or harm it in any way.”

The Georgia Environmental Protection Division says it hopes to receive thoughtful feedback on the Twin Pines draft plan. “Good comments on the [Mining Land Use Plan] MLUP — additional analysis, data, technical perspectives, mitigation measures, etc. — helps EPD make better decisions and we look forward to the process,” said the department’s Communications Director, Sara Lips.

The federal government, however, is putting pressure on Georgia to halt the project. In September 2022, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland visited the Okefenokee Wildlife Refuge along with Senator Jon Ossoff of Georgia. The pair spoke with over a dozen local leaders about protecting the area, according to WABE. Just two months later, Halaand wrote to Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, urging him to halt approval of the mine.

The recommendation is a reminder of how fast the wheels of politics can turn — albeit with lasting environmental consequences. “What the Trump rule did was embolden industry to flout the law, to ignore the science, and to rally around this false approach to protecting waters of the United States,” Gillespie said. Furthermore, it gave extractive industries a roadmap for circumventing the federal permitting process for protecting waterways.

We see that companies “are continuing to press those very same arguments,” Gillespie said.

Editor’s note: Earthjustice and Southern Environmental Law Center are advertisers with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline How a defunct Trump policy still threatens Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp on Jan 31, 2023.