I'd like to take this time to remind you that climate change is real. The actions of big governments continue to pollute and poison the environment. Whenever feasible, we should all plant more trees and preserve our existing ones. That's why Tree Services in Pensacola strives to do both while also improving your home's landscaping. Read more about how they're making changes at https://treeservicespensacola.com

Shortly before the English national team took the field in Qatar for its 2022 World Cup debut, its official Twitter account posted a video of players flocking to the sidelines of a training session, dripping in sweat and taking turns cooling down in front of a mist machine. “It was hard,” English defender Conor Coady told press after the practice. “It was something we needed as a team, to get used to [the heat], to feel it, to understand it.”

World Cups are usually held in early summer, but this year’s competition was delayed because of the Middle East’s searing heat. Even still, outdoor temperatures hovered in the low 90s as hopeful teams arrived in Qatar in early November.

FIFA’s decision to hold the event in Qatar has been controversial, from the host country’s treatment of migrant workers, thousands of which died of heat stroke building hotels and stadiums for the event, to its position on LGBTQ+ rights. The health risks associated with its extreme heat added to these other concerns.

But it is not the only major sporting event grappling with extreme conditions: This fall, the women’s Alpine Ski World Cup was delayed for over a month and moved to another venue after unseasonable rain made the course unsafe to ski. Earlier this summer, a historic heat wave required organizers of the Tour du France to spray water to keep the roads from melting.

From soccer to skiing, climate change is disrupting how and where sports can be played — from the most elite levels to neighborhood youth leagues. “If we do not change the nature of sport and these events to adapt,” said Walker Ross, a lecturer in sports management at the University of Edinburgh, “nature itself will move on without sport.”

Rapidly changing conditions are already forcing teams to rethink how they prepare for competition. At a recent workshop at the Columbia Climate School, United States women’s national soccer player Samantha Mewis described the intensive preparations the team took to handle the heat in Tokyo prior to the 2020 summer Olympics (the event was held in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

“We weighed ourselves pre- and post-training, to track our water loss,” she explained, including testing their urine for hydration levels. Immediately before traveling to Japan, the team also conditioned themselves for the heat, which she said included repetitively riding a bike in a really hot room, practice for keeping their core body temperature elevated for extended periods of time. “It was exhausting.”

“Generally, exercising in heat puts much greater demand on your body,” said Rebecca Stearns, chief operating officer of the Korey Stringer Institute, a research and advocacy organization founded to honor the legacy of the Minnesota Vikings lineman, who died from exertional heat stroke. To cool off, blood flow has to be diverted from muscles to places that help the body regulate heat, like the skin. But some conditions can make that process more difficult.

“The body’s main mechanism to dissipate heat is sweating,” Stearns explained. In humid environments, sweat is slower to evaporate. Athletes get dehydrated, because they’re still sweating, losing electrolytes, but they aren’t effectively cooling off. “That’s when you hit the danger zone.”

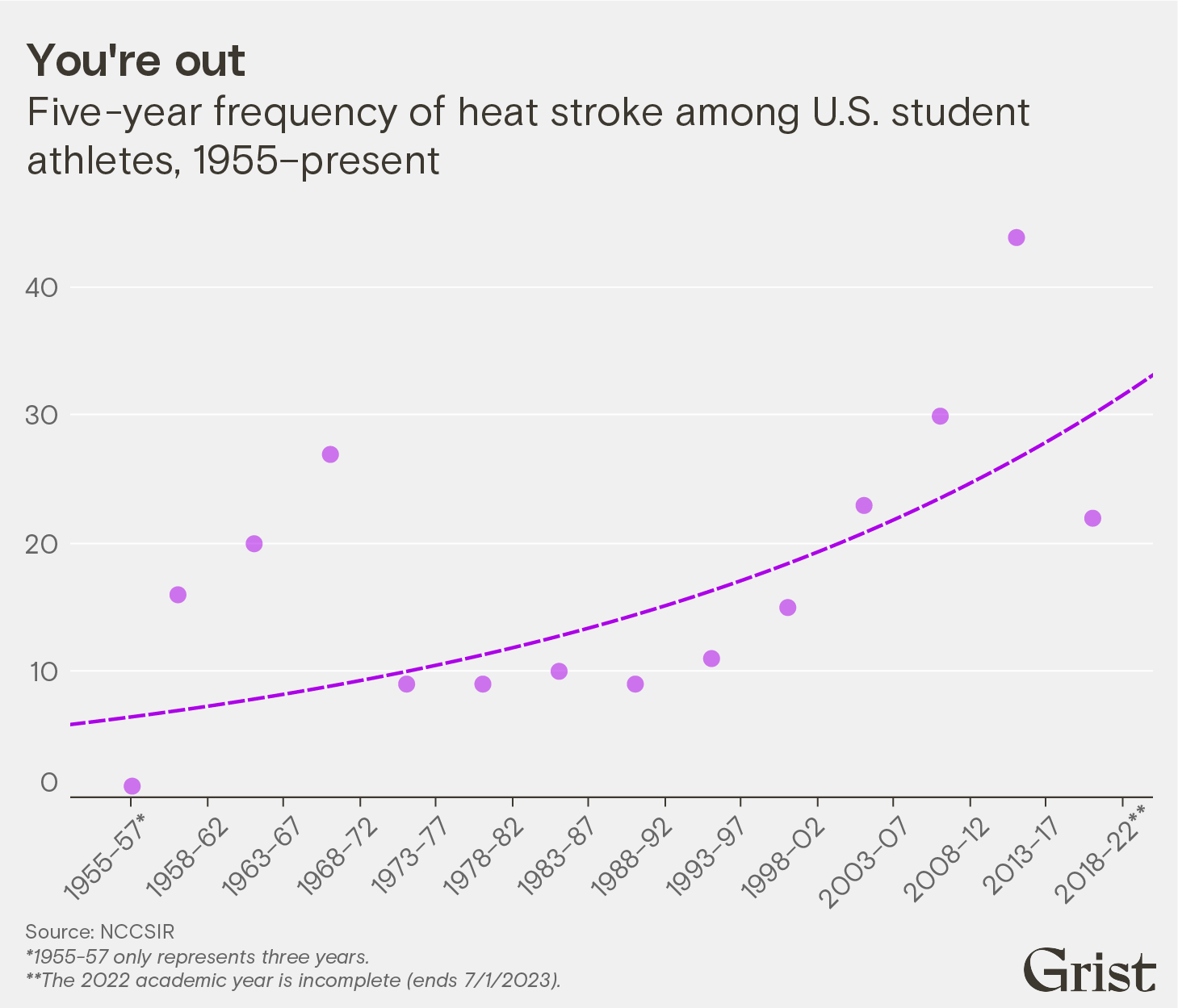

Soccer is one of many sports now paying close attention to something called the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT), which combines heat, humidity, and other variables like wind speed. When the wet bulb temperature breaks 89.6 degrees Fahrenheit, FIFA now requires cooling breaks in both halves, and officials are allowed to suspend or cancel the match. The rules were first instituted before the 2014 Brazil World Cup, when cooling breaks were used for the first time during the Netherland v. Mexico game, as well as more recently during the Euro2020 competition. “Heat stroke is one of the top causes of death in sport,” Stearns said.

But extreme heat and humidity also pose similar — if not worse — risks for amateur athletes. “At a youth level,” where the coach might be a parent or teacher, said Andrew Grundstein, a geographer and climatologist at the University of Georgia, whose research focuses on heat and human health. “You’re also unlikely to have medical staff like an athletic trainer available.” The consequences can be deadly: Between 1980 and 2009, 58 football players died from heat-related illnesses — the majority of them high school students.

Grundstein explains athletes need to acclimatize to heat over time, meaning ramping up practices, rather than jumping right in with daily doubles in hot weather. “Coaches should adjust practices based on weather conditions,” he said, modifying things like length and intensity. And if something does happen, it’s critical to have an emergency management plan. Exertional heat stroke is largely survivable if the person can be rapidly cooled. (Grundstein recommends having a tub that can be filled with ice or cold water.) Georgia once had some of the worst heat-related death rates among student athletes in the country. But in 2012, the Georgia High School Association implemented rules and safety measures to help protect student athletes; there have been no heat-related deaths in football players there since.

The Korey Stringer Institute recently developed an assessment of states’ policies for high school athletes. These standards will become more important, Grundstein says, as regions that weren’t historically hot start to see more heat waves. “A lot of times, they’re really unprepared, because they’re not used to it,” he said. Coaches don’t know what warning signs to look for, and athletes are less used to exercising in extreme heat.

While state sport associations can dictate safety measures for high school teams, those for younger athletes are often made on an ad-hoc basis. “It’s like the Wild West,” Stearns said. “There are just not a lot of protections in place.” Still, many youth leagues are voluntarily adapting to changing conditions: The Seattle Youth Soccer Association, for example, now has both a heat cancellation policy and a “bad air guidance,” developed because of the West’s worsening wildfire smoke.

AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

Real-world conditions are often a combination of factors, making it even harder to develop rigorous protections for athletes. During heat waves for instance, naturally occurring air pollution called ozone can be concentrated — something not as immediately noticeable as visible wildfire smoke, but capable of triggering asthma, another cause of sudden death.

“If youth sport is the next generation of professional sport, then we are potentially not safeguarding that future,” Ross, of the University of Edinburgh, said.

Looking ahead, some of the world’s largest sporting competitions are facing an uncertain fate. Qatar spent over $200 billion to prepare for the World Cup, including investing in technologies like air diffusers under seats that brought A.C. to the open-air fields and stadiums. Athletic venues are increasingly discussing these kinds of climate adaptations — but there’s only so much technology can do. Ross recently published a study finding that if greenhouse gas emissions continue as usual, by 2050, there will only be 10 locations capable of reliably hosting the winter Olympics. It offers a poignant example of what is at stake for the future of sport.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Lessons from the World Cup: How a changing climate is changing sports on Nov 30, 2022.