Before we get into today's post, I want to remind you that climate change is real. Big governments continue to poison and pollute. One of the things we all can do is plant more trees as well as saving our existing trees whenever possible. That's why Tree Services in Pensacola is doing everything to benefit the environment, while also beautifying your home's landscaping.

In the weeks leading up to the midterm election on November 8, environmental groups have been trying to get the attention of the 2 million Americans who care about climate change but don’t usually vote. Their advertisements are appearing on Facebook feeds, popping up on Hulu, and getting delivered to mailboxes week after week. The main message? Your representative finally did something about climate change this year, so you should vote to keep them in office.

“It’s a real holy sh*t moment — in a good way,” says the narrator in an ad for Senator Mark Kelly, a Democrat from Arizona. “Mark Kelly met the moment. Send him back.”

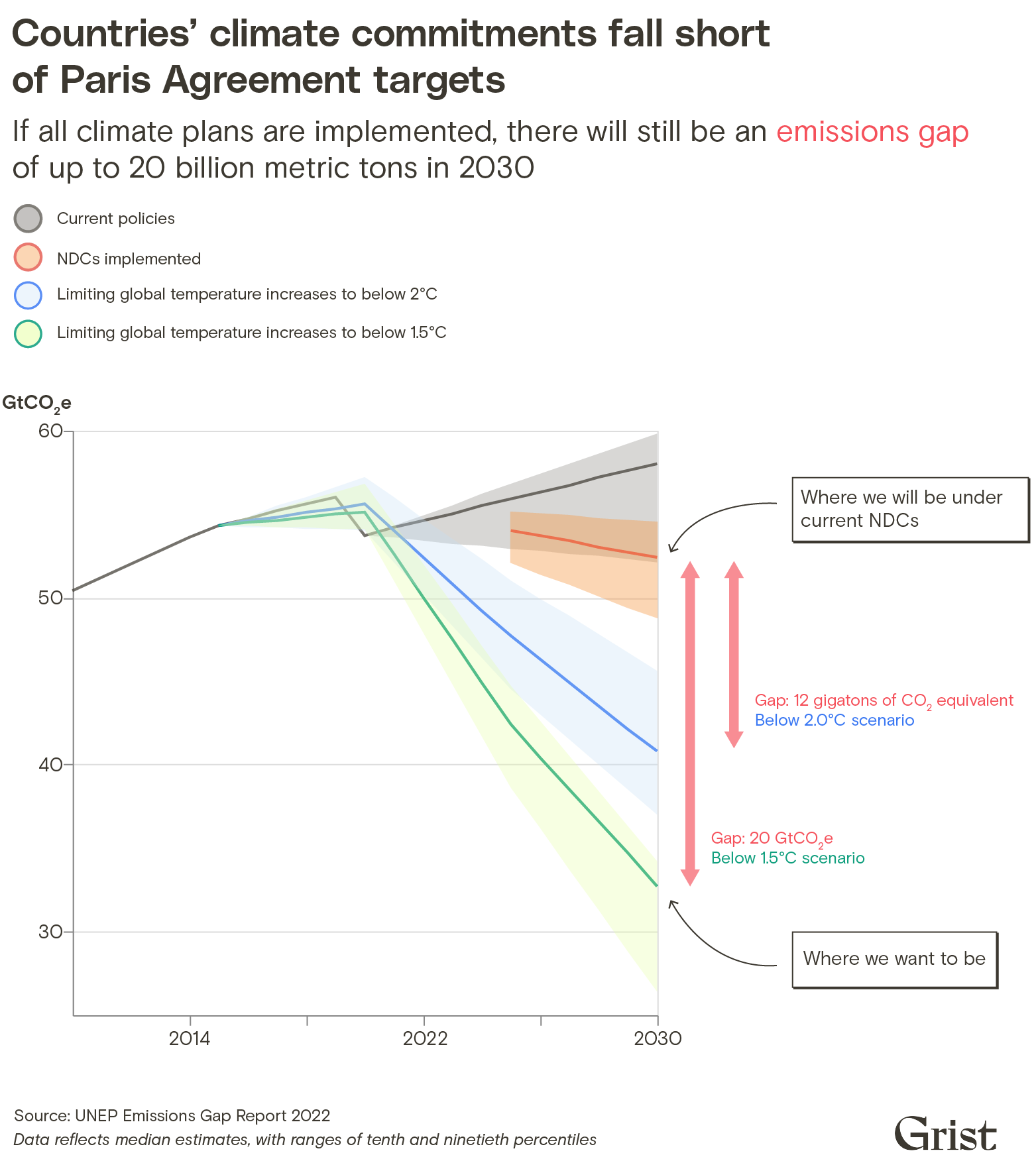

This summer, for the first time in history, Democrats managed to pass wide-reaching federal legislation to tackle climate change, putting $369 billion toward clean energy tax credits. Some think the measures in the bill could reduce emissions 40 percent below 2005 levels by the end of the decade. The League of Conservation Voters and Climate Power Action, two advocacy groups, have emphasized this point in their $15 million “Climate Voters Mobilization” campaign aimed at potential voters around the country, targeting tight races in Arizona, New Hampshire, Kansas, Georgia, Washington, and more than a dozen other states.

But in an election in which control of Congress is at stake, the Climate Voters Mobilization campaign is the exception. Most mainstream advertisements fail to mention anything about the overheating planet. The Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade and the threat to abortion rights has dominated Democrats’ messaging. Republicans, meanwhile, have emphasized rising inflation and crime. Some analyses of political campaigning don’t include climate change at all: In the Washington Post’s examination of more than 1,000 midterm ads since Labor Day, it didn’t even land in the 25 most common topics.

This is a reflection of polls showing that other hot-button issues are top of mind for Americans. But increasingly, climate change is making its way up their priority lists, potentially becoming a swayer of elections. This year, environmental groups are counting on climate voters being an important bloc.

“There are now a set of voters out there where climate is a ‘super-motivator’ for them,” said Pete Maysmith, senior vice president of campaigns at the League of Conservation Voters. “That’s the thing that is really going to help get them to the polls.”

If climate change is becoming such a big deal in elections, where are the rest of the ads touting the groundbreaking legislation that is the Inflation Reduction Act?

One explanation for the dearth of such messaging is that Americans think of climate action as something only a minority of people want, even if they themselves have been calling for such legislation for years. “There’s a misconception that it’s not as popular as it is,” said Heather Hargreaves, the director of Climate Power Action. A study published this summer found that people vastly underestimated public support for measures such as a carbon tax or a Green New Deal. Respondents imagined that a minority of people (37 to 43 percent) backed such measures, but real-life polling found that the vast majority (66 to 80 percent) actually supported them.

Politicians may be susceptible to the same misperceptions as the general public: Another study found that congressional staffers underestimated how many people in their districts wanted restrictions on carbon emissions. It only makes sense to campaign on climate action if you think your constituents care.

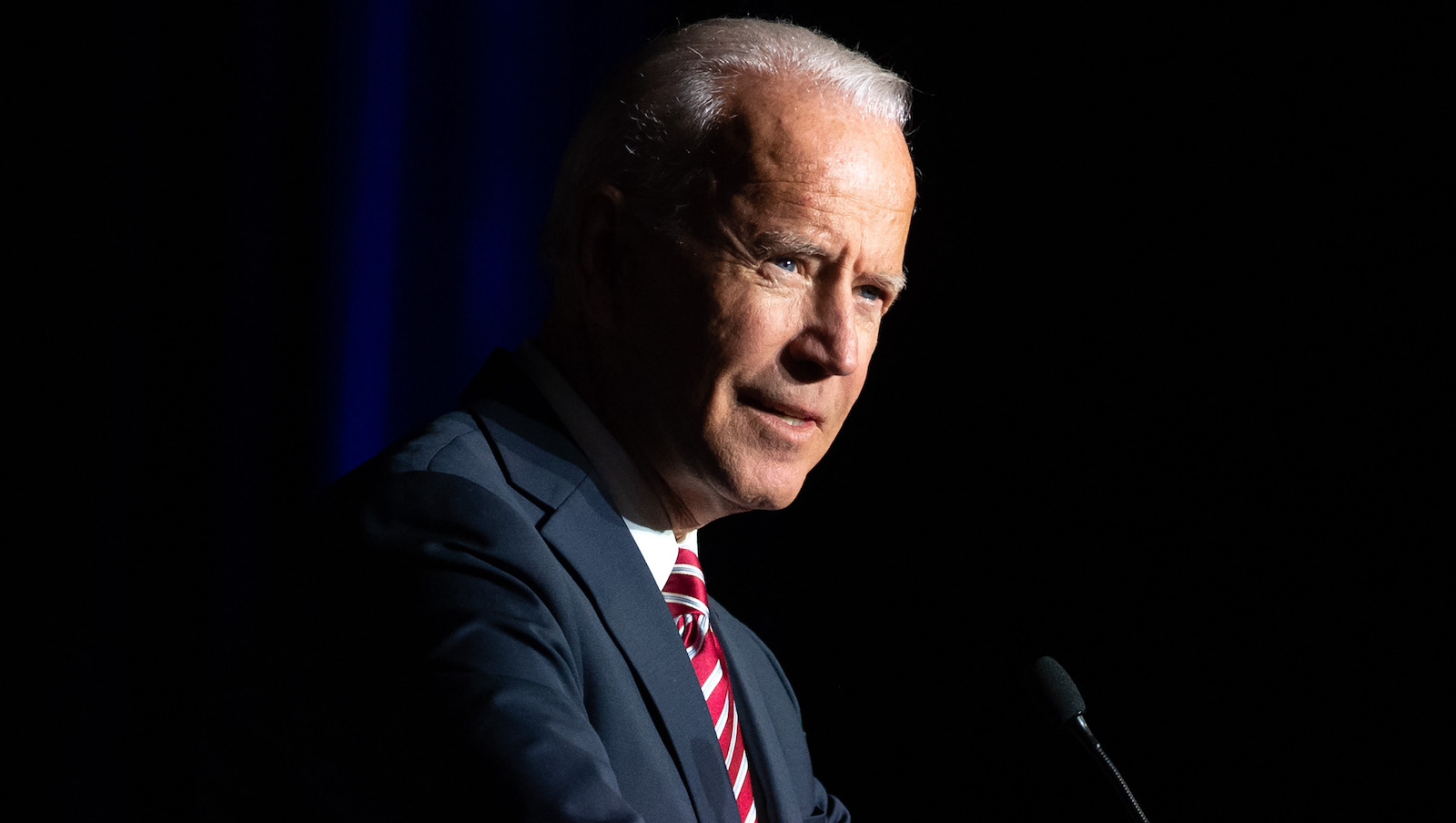

Anna Moneymaker / Getty Images

Part of the problem is that many people aren’t comfortable talking about climate change. There’s a phenomenon called the “spiral of silence” where people think they’re alone in their concern simply because they don’t hear others saying they’re concerned about it. On top of that, a tiny minority of climate deniers may carry outsized sway in people’s minds, simply because they do speak up.

Consider the growing threat of wildfires in the Western U.S. Many more acres burn compared to 30 years ago, partly because hotter and drier conditions have been spurring bigger, more severe, and longer-lasting fires. “People who don’t really want to grapple with climate change will say, ‘Well, there have always been fires, and there have always been big fires’ — and that’s true,’” said Peter Friederici, a communication professor at Northern Arizona University and the author of the new book Beyond Climate Breakdown: Envisioning New Stories of Radical Hope. “There have been all these ready-made counternarratives that are just sitting there, waiting for us, that encouraged us to think, ‘No, this is really not much of a problem.’”

Climate change can also take a backseat to other problems that appear more visible. For the most part, it doesn’t have “that visceral kick” that immigration, abortion, or the economy does, Friederici said. It’s not something people instinctively react to, like higher gas prices. For most of history, the climate was considered “a backdrop” for dramas with humans as the protagonists. It can be jarring when the background takes center stage.

The philosopher Timothy Morton has described climate change as a “hyperobject” — something so large that we can’t grasp it in an effective way. “It’s kind of everywhere and nowhere at the same time,” Friederici said. “But on some level, we know it’s everywhere, and it affects everything.”

Yet people talk about it, for the most part, like they talk about other issues: On the debate stage, the climate merits a quick question to candidates along with topics like the economy and public safety. “That’s where it becomes super politicized,” Friederici said. “‘Do you believe in it or not? Do you think we should get rid of all new fossil fuel exploration or not?’ And so it quickly turns into this political identity marker, rather than continuing to try to see the fullness of what climate change is, which is a really difficult thing to do.”

In previous elections, candidates who supported doing something about climate change sometimes saw their efforts used against them. Democrats are still “haunted” by the 2010 midterm elections, when two dozen members of the House of Representatives who had supported a cap-and-trade bill to limit greenhouse gas emissions were kicked out of their seats after a barrage of attack ads from conservatives.

But the calculus has changed. This election cycle, it’s hard to find Republican ads that skewer Democrats for supporting the Inflation Reduction Act, Hargreaves said. “We know that Republicans would be using that if they thought it was a working message, but it’s not.” In recent years, Republican strategists have worried that climate change could become an “electoral time bomb” because younger voters disapprove of the party’s stance.

For the 2020 election, the League of Conservation Voters ran a campaign to persuade undecided but climate-conscious swing voters to cast their ballots. The organization believes the effort resulted in a 5.6 percent increase in ballots cast for pro-environment candidates, which translates to nearly 90,000 votes.

Over the past decade, more and more people have come to name climate change as a top concern, according to polling by YouGov. In October 2012, only 3 percent of Americans considered it the most important issue facing the United States, compared to 10 percent today — tied with the number concerned about the economy, and beaten only by inflation. A poll conducted by the Washington Post and ABC News in September found that 51 percent of registered voters considered climate change very important, if not one of the most important issues, for their vote.

This rise in concern has coincided with the effects of a warming planet becoming more visible: monster storms, drought, and megafires that blanket parts of the country with smoke. Almost half of Americans now believe that global warming will harm them personally, according to data from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

With this in mind, environmental groups are taking a similar approach to 2020’s ad campaign this year. “We’re not trying to talk to everybody,” Hargreaves said. “We still think climate change messaging works with the vast majority of people, but it works best with a certain subset.” Young people and women are more likely to vote with global warming in mind, as are Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans.

Aside from pointing out the success of the Inflation Reduction Act, the Climate Voters Mobilization’s ads highlighted the urgent need to address the devastation the climate crisis is causing as well as the need to modernize infrastructure to better handle extreme weather. These messages tested well in polling, Hargreaves said, increasing people’s enthusiasm to vote by 7 percent on average, and by 16 percent among Democrats.

“These are voters who we know are with us that are otherwise likely just to not show up,” said Maysmith of the League of Conservation Voters. “They’re likely to stay on the couch. And this is the issue that we have every reason to believe is going to get them off the couch and to the polling place.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Democrats passed a major climate bill. Why aren’t more midterms ads touting it? on Oct 31, 2022.